Ensemble Tirana (Albania)

Ura qe Lidh Motet (2014)

18 tracks, 65 minutes

Spotify • iTunes

There are traditions of polyphonic choral singing all over the world, and it’s always glorious. It’s what unites vocal traditions from Gaelic psalm singing on the Isle of Lewis to the Dong people of south-west China to the Aka and Baka of central Africa; there are particularly revered styles from Corsica and Georgia that have long been known to international audiences. There’s just something about many voices singing so tightly together yet independently, where there is always multiple melodies occurring at once and quite often several harmonies interacting too, that inspires quiet awe.

By far my favourite polyphonic tradition, however, is that of Albanian iso-polyphony, which is showcased wonderfully by Ensemble Tirana on this album. Iso-polyphony is based around sung drones; from these drones blossom melodies and countermelodies that always reference back to the drone, creating ever-shifting patterns of harmonies throughout. The singers’ voices are occasionally strident, but they are more often hushed and soft, sometimes barely at a whisper, which, in combination with the harmonies, makes the whole thing feel so delicate; the fact that the singers frequently flip into head-voice just adds to that feeling, and helps to raise the hairs on the back of your neck. Something I particularly enjoy about this sort of music – because it’s my weakness – is just how bluesy it is. So much of the melody is in a minor pentatonic anyway, but then the way that the singers slide down their thirds is pure delta. Stick a blues singer like Skip James or Junior Kimbrough up front among those Albanians and their tunes would slot in perfectly.

Although the a cappella iso-polyphony is Ensemble Tirana’s speciality, Ura qe Lidh Motet also contains several other styles, both choral and instrumental. There are a few nice examples of pieces on the çifteli (reminiscent in some ways of the Turkish bağlama), but of the instrumental contributions, it is the track ‘Ju Pampore qe Shkoni’ that really gets me, where the standard iso-polyphony is joined by a kaval flute playing in lovely soft and breathy tones. The flute adds to the intricate harmonies, while adding its own timbral dimension.

Polyphonic singing is one of the world’s musical wonders, and the Albanian style is surely the jewel in its crown. How else to describe such an intense choral tradition that sounds like it could come from anywhere from ancient Anatolia to the deepest Mississippi? Now all we need is to get some blues singers involved…

My 2019 challenge: I'm going to post a little something about an album (or somesuch) that I like every single day. Written by Jim Hickson.

Tuesday, 30 April 2019

Monday, 29 April 2019

119: Soyo, by Dom La Nena

Dom La Nena (Brazil)

Soyo (2015)

11 tracks, 39 minutes

Bandcamp • Spotify • iTunes

Although I try to be as open-eared as possible, there are certain cultures in the world whose music I just struggle to connect with. I’ve mentioned it before in regards to South Africa, but there’s still a few South African musical styles that I enjoy more often than not. Less so with music from Brazil. For such a huge country with so many subcultures within, I can’t help but find the vast majority of Brazilian music that I’ve heard completely uninspiring, at best. The chords and their changes are too smooth, the rhythms repetitive and the melodies either lacking in personality or filled with smugness. Even the massed percussion of the samba leaves me bored, and don’t get me started on bossa nova. These are definitely sweeping statements, probably unfair ones at that, but it’s disappointing how widely they seem to ring true.

What’s weird is that, in Soyo, Dom La Nena’s music has all the elements that I usually dislike in Brazilian music. The music here is nice – and that’s usually a bad thing! But…it’s good! Really good. So what gives? No idea. In fact, there’s also a really twee pop sensibility about it, too: there’s ukuleles, glockenspiels, half-whispered vocals and loads of compression, to the degree that most of the tracks wouldn’t feel too out-of-place on an advert for organic yoghurt. So much of the stylistic influence on offer here is inoffensive, but Dom brings an edge to it. I’m not sure what it is. I think it may be that the execution is less overly earnest than others of its style, while still being obviously heartfelt.

It’s really lovely music for relaxing to. It makes me think of a sunny Sunday morning in the summer, eating breakfast on the cool grass. There’s nothing too energetic, but it’s not sleepy either, the atmospheres are constructed so well. There always seems to be quite a lot going on in terms of chords, melodies, countermelodies, shuffling samba-esque rhythms, little ephemeral production elements here and there, but it never sounds busy. It all slots in just right. Then of course there’s Dom’s voice, which is really soft and fragile, and complements those textures well; there's even a touch of Billie Holiday about her. It’s especially pleasing when she adds her own vocal harmonies by the miracle of overdubs.

So yeah. Twee pop with a distinctly Brazilian edge with airy vocals over the top…despite it being everything I’d usually avoid, this album hits me exactly right. Never be afraid to listen to that artist you think you’ll hate, whoever it may be. They may surprise you.

Soyo (2015)

11 tracks, 39 minutes

Bandcamp • Spotify • iTunes

Although I try to be as open-eared as possible, there are certain cultures in the world whose music I just struggle to connect with. I’ve mentioned it before in regards to South Africa, but there’s still a few South African musical styles that I enjoy more often than not. Less so with music from Brazil. For such a huge country with so many subcultures within, I can’t help but find the vast majority of Brazilian music that I’ve heard completely uninspiring, at best. The chords and their changes are too smooth, the rhythms repetitive and the melodies either lacking in personality or filled with smugness. Even the massed percussion of the samba leaves me bored, and don’t get me started on bossa nova. These are definitely sweeping statements, probably unfair ones at that, but it’s disappointing how widely they seem to ring true.

What’s weird is that, in Soyo, Dom La Nena’s music has all the elements that I usually dislike in Brazilian music. The music here is nice – and that’s usually a bad thing! But…it’s good! Really good. So what gives? No idea. In fact, there’s also a really twee pop sensibility about it, too: there’s ukuleles, glockenspiels, half-whispered vocals and loads of compression, to the degree that most of the tracks wouldn’t feel too out-of-place on an advert for organic yoghurt. So much of the stylistic influence on offer here is inoffensive, but Dom brings an edge to it. I’m not sure what it is. I think it may be that the execution is less overly earnest than others of its style, while still being obviously heartfelt.

It’s really lovely music for relaxing to. It makes me think of a sunny Sunday morning in the summer, eating breakfast on the cool grass. There’s nothing too energetic, but it’s not sleepy either, the atmospheres are constructed so well. There always seems to be quite a lot going on in terms of chords, melodies, countermelodies, shuffling samba-esque rhythms, little ephemeral production elements here and there, but it never sounds busy. It all slots in just right. Then of course there’s Dom’s voice, which is really soft and fragile, and complements those textures well; there's even a touch of Billie Holiday about her. It’s especially pleasing when she adds her own vocal harmonies by the miracle of overdubs.

So yeah. Twee pop with a distinctly Brazilian edge with airy vocals over the top…despite it being everything I’d usually avoid, this album hits me exactly right. Never be afraid to listen to that artist you think you’ll hate, whoever it may be. They may surprise you.

Sunday, 28 April 2019

118: Fofoulah, by Fofoulah

Fofoulah (United Kingdom/Senegal/Gambia)

Fofoulah (2014)

9 tracks, 40 minutes

Bandcamp • Spotify • iTunes

As the brainchild of a jazz drummer with an intense interest in West African drumming, it’s no wonder that Fofoulah’s sound is so rhythmically intense. The group was formed by Dave Smith, who’s currently best known as the drummer for Robert Plant after the Led Zep man absorbed the brilliant Afro-blues trance group JuJu into his own Sensational Space Shifters. Smith became a major force in the UK jazz scene before becoming obsessed with the Senegambian sabar drums and their amazingly complex rhythms.

So that’s where Fofoulah’s music starts. The drums are all-important, and between Smith on drum kit and Gambian percussionist Kaw Secka on the tama talking drum – and both with the sabar – they create whole soundworlds just out of skin, stick and finger. The polyrhythms shift constantly throughout, a brilliant mix of traditional West African styles and jazz, and with other incursions from dub and hip-hop. That basis informs the rest too, which layers up Wolof songs with astro-jazz solos, synthscapes and highlife-informed guitars.

There’s also great contributions here from Tom Challenger, a great sax player who straddles jazz and classical worlds (and occasionally looks disconcertingly like an older version of me) and Batch Gueye, a Wolof griot who’s become an important part of the UK African music scene, as well as guest musicians Juldeh Camara, Iness Mezel and Ghostpoet.

Fofoulah was the group’s first album and they absolutely burst onto the scene with it – it sounds much more accomplished and assured than a debut would lead you to believe, and I do think a big part of that is Smith’s rhythmic wizardry. They’ve not long come out with a second album, Daega Rek, which I’ve not managed to listen to yet, but I’m interested to find out how four years of touring and maturing have changed their sound.

Fofoulah (2014)

9 tracks, 40 minutes

Bandcamp • Spotify • iTunes

As the brainchild of a jazz drummer with an intense interest in West African drumming, it’s no wonder that Fofoulah’s sound is so rhythmically intense. The group was formed by Dave Smith, who’s currently best known as the drummer for Robert Plant after the Led Zep man absorbed the brilliant Afro-blues trance group JuJu into his own Sensational Space Shifters. Smith became a major force in the UK jazz scene before becoming obsessed with the Senegambian sabar drums and their amazingly complex rhythms.

So that’s where Fofoulah’s music starts. The drums are all-important, and between Smith on drum kit and Gambian percussionist Kaw Secka on the tama talking drum – and both with the sabar – they create whole soundworlds just out of skin, stick and finger. The polyrhythms shift constantly throughout, a brilliant mix of traditional West African styles and jazz, and with other incursions from dub and hip-hop. That basis informs the rest too, which layers up Wolof songs with astro-jazz solos, synthscapes and highlife-informed guitars.

There’s also great contributions here from Tom Challenger, a great sax player who straddles jazz and classical worlds (and occasionally looks disconcertingly like an older version of me) and Batch Gueye, a Wolof griot who’s become an important part of the UK African music scene, as well as guest musicians Juldeh Camara, Iness Mezel and Ghostpoet.

Fofoulah was the group’s first album and they absolutely burst onto the scene with it – it sounds much more accomplished and assured than a debut would lead you to believe, and I do think a big part of that is Smith’s rhythmic wizardry. They’ve not long come out with a second album, Daega Rek, which I’ve not managed to listen to yet, but I’m interested to find out how four years of touring and maturing have changed their sound.

Saturday, 27 April 2019

117: Let The Good Times Roll: The Music of Louis Jordan, by B.B. King

B.B. King (USA)

Let The Good Times Roll: The Music of Louis Jordan (1999)

18 tracks, 60 minutes

Spotify • iTunes

Louis Jordan was a fantastic musician who has been featured on this blog before. Of course, I love his work, and it’s clear that I’m not the only one. Jordan had/has legions of famous fans and his compositions and influence spread far and wide. This album of B.B. King playing 18 of Louis Jordan’s hits is a great example of this.

This was another album purchased at that gone-and-apparently-forgotten Lyme Regis second-hand record shop that always seemed to have some gold in it, and I remember being absolutely thrilled when I found this album in their racks, and I wasn’t disappointed. Where Jordan’s originals were a midpoint between blues and jazz, B.B. skews it towards the former, and it’s really nice to hear that subtle difference as opposed to just a bunch of straight-up covers. The jazz isn’t abandoned, and the contributions of some great musicians help to keep the music sited within the jive realm, but B.B.’s immediately recognisable guitarwork and vocals add a special edge to the whole thing.

I also have to mention the great work of Dr John on this album. He plays piano throughout, and adds guest vocals to the song ‘Is You Is Or Is You Ain’t My Baby’, adding a wry irony to the original song’s plot, along with his own absolutely delicious Louisiana accent. Dr John is an artist that I absolutely love in general, and to hear him playing alongside a legend like B.B. King and performing all the hits from another of my favourite artists is just great. That song is so good, it even ended up winning a Grammy all to itself, for ‘Best Pop Collaboration with Vocals.’

Cover albums can sometimes be a bit hit-and-miss, but a legendary blues guitarist playing the songs of probably the best jump-jive composer ever, with wonderful contributions from an amazing New Orleans pianist…well, I’m not too surprised that this album turned out so well.

Let The Good Times Roll: The Music of Louis Jordan (1999)

18 tracks, 60 minutes

Spotify • iTunes

Louis Jordan was a fantastic musician who has been featured on this blog before. Of course, I love his work, and it’s clear that I’m not the only one. Jordan had/has legions of famous fans and his compositions and influence spread far and wide. This album of B.B. King playing 18 of Louis Jordan’s hits is a great example of this.

This was another album purchased at that gone-and-apparently-forgotten Lyme Regis second-hand record shop that always seemed to have some gold in it, and I remember being absolutely thrilled when I found this album in their racks, and I wasn’t disappointed. Where Jordan’s originals were a midpoint between blues and jazz, B.B. skews it towards the former, and it’s really nice to hear that subtle difference as opposed to just a bunch of straight-up covers. The jazz isn’t abandoned, and the contributions of some great musicians help to keep the music sited within the jive realm, but B.B.’s immediately recognisable guitarwork and vocals add a special edge to the whole thing.

I also have to mention the great work of Dr John on this album. He plays piano throughout, and adds guest vocals to the song ‘Is You Is Or Is You Ain’t My Baby’, adding a wry irony to the original song’s plot, along with his own absolutely delicious Louisiana accent. Dr John is an artist that I absolutely love in general, and to hear him playing alongside a legend like B.B. King and performing all the hits from another of my favourite artists is just great. That song is so good, it even ended up winning a Grammy all to itself, for ‘Best Pop Collaboration with Vocals.’

Cover albums can sometimes be a bit hit-and-miss, but a legendary blues guitarist playing the songs of probably the best jump-jive composer ever, with wonderful contributions from an amazing New Orleans pianist…well, I’m not too surprised that this album turned out so well.

Friday, 26 April 2019

116: Forest Bathing, by A Hawk and a Hacksaw

A Hawk and a Hacksaw (USA)

Forest Bathing (2018)

10 tracks, 34 minutes

Bandcamp • Spotify • iTunes

This album is one of those ones that caught my attention just by being something that I didn’t expect at all. I came across this album when I was randomly asked to make a short write-up about them last year. I had heard of A Hawk and a Hacksaw before, as they’d been around for quite a while (they released their first album back in 2002). I’d never actually heard their music though, and for some reason I’m not entirely clear on, I figured they were some sort of ethereal indie-Americana-folky sort of outfit. That’s not what you get on Forest Bathing.

What you do get is a relaxed and refined set that takes heavy influence from Hungarian and Bulgarian Romani music, Balkan brass, klezmer and even Arabic pop and classical styles. It is quite ethereal though, so I was right on that; it works well with that theme of ‘forest bathing,’ a way of relaxing and enjoying nature by connecting with the forest. It is interesting that the instruments that are used are sometimes those with quite harsh or bold tones – such as a cimbalom, a brass ensemble, some very Omar Souleyman-like synthesisers and a really odd sound that I think is produced by dragging a single horse hair across a fiddle string, giving a scratchy, hollow sound – but the context in which the duo use them render them as gentle as anything.

The thing that solidifies this album’s inclusion on this list for me is that it includes a melody that gets stuck in my head out of nowhere all the time. It gets stuck for ages, as well, and I always forget where I know it from. It’s not even an unpleasant experience; it’s a really beautiful melody. Then I realise it’s from this album and get to enjoy it all over again. If you want to inflict this condition upon yourself, it’s the melody from the fourth track, ‘The Shepherd Dogs are Calling’.

I love coming across something unexpected. I don’t even know the rest of the band’s discography, so for all I know, their other stuff may well be that ethereal indie-Americana-folky stuff that I thought at first, although I doubt it. Either way, it’s always fun to be taken on a musical adventure that you were just completely unprepared for, and A Hawk and a Hacksaw did that for me in the form of Forest Bathing. Come to think of it, maybe I’ve prepared you too well, just by writing this. Sorry about that. Listen to it anyway.

Forest Bathing (2018)

10 tracks, 34 minutes

Bandcamp • Spotify • iTunes

This album is one of those ones that caught my attention just by being something that I didn’t expect at all. I came across this album when I was randomly asked to make a short write-up about them last year. I had heard of A Hawk and a Hacksaw before, as they’d been around for quite a while (they released their first album back in 2002). I’d never actually heard their music though, and for some reason I’m not entirely clear on, I figured they were some sort of ethereal indie-Americana-folky sort of outfit. That’s not what you get on Forest Bathing.

What you do get is a relaxed and refined set that takes heavy influence from Hungarian and Bulgarian Romani music, Balkan brass, klezmer and even Arabic pop and classical styles. It is quite ethereal though, so I was right on that; it works well with that theme of ‘forest bathing,’ a way of relaxing and enjoying nature by connecting with the forest. It is interesting that the instruments that are used are sometimes those with quite harsh or bold tones – such as a cimbalom, a brass ensemble, some very Omar Souleyman-like synthesisers and a really odd sound that I think is produced by dragging a single horse hair across a fiddle string, giving a scratchy, hollow sound – but the context in which the duo use them render them as gentle as anything.

The thing that solidifies this album’s inclusion on this list for me is that it includes a melody that gets stuck in my head out of nowhere all the time. It gets stuck for ages, as well, and I always forget where I know it from. It’s not even an unpleasant experience; it’s a really beautiful melody. Then I realise it’s from this album and get to enjoy it all over again. If you want to inflict this condition upon yourself, it’s the melody from the fourth track, ‘The Shepherd Dogs are Calling’.

I love coming across something unexpected. I don’t even know the rest of the band’s discography, so for all I know, their other stuff may well be that ethereal indie-Americana-folky stuff that I thought at first, although I doubt it. Either way, it’s always fun to be taken on a musical adventure that you were just completely unprepared for, and A Hawk and a Hacksaw did that for me in the form of Forest Bathing. Come to think of it, maybe I’ve prepared you too well, just by writing this. Sorry about that. Listen to it anyway.

Thursday, 25 April 2019

115: Bagpuss: The Songs and Music, by Sandra Kerr & John Faulkner

Sandra Kerr & John Faulkner (United Kingdom)

Bagpuss: The Songs and Music (1999)

21 tracks, 44 minutes

Spotify • iTunes

There has actually just been a recent release called The Music from Bagpuss on Earth Recordings, which should not be confused with this album, Bagpuss: The Songs and Music, which is from 1999. The newer release has different recorded versions of the same tracks, as well as a bunch more. But the earlier one is the one that I know, so it’s that one I’m writing about here.

And it is the album that I know. I’m not old enough to have watched Bagpuss as a kid, and I’ve since only ever caught glimpses of it on clip shows and the like. I actually rather stumbled upon this album, after hearing a very small snippet of a piece from it on a telly programme by Charlie Brooker and wanting to hear more of it. I wasn’t expecting it to be such a full-on folk fest. This happened during my slow blossoming into a folk music fan (which I’ve discussed a little before) and this album certainly helped me along the way.

The music really does reflect the nature of animator Oliver Postgate’s work: it is utterly charming and delightfully whimsical. There are silly little songs like the ‘mouse rounds’ (rounds, sung by mice, of course), to songs that would sound traditional if their subject matter was ever-so-slightly less surreal, such as ‘Uncle Feedle’ and ‘The Bony King of Nowhere’. There’s also occasional little spoken word bits and pieces from the wonderfully rounded voice of Postgate himself. It’s all so comforting and relaxing, and although the music’s themes are obviously child-friendly, the music itself is not dumbed down for the younger audience at all. This respect for its audience also means that Bagpuss: The Songs and Music is a fulfilling listen for music fans of any age.

Bagpuss: The Songs and Music (1999)

21 tracks, 44 minutes

Spotify • iTunes

There has actually just been a recent release called The Music from Bagpuss on Earth Recordings, which should not be confused with this album, Bagpuss: The Songs and Music, which is from 1999. The newer release has different recorded versions of the same tracks, as well as a bunch more. But the earlier one is the one that I know, so it’s that one I’m writing about here.

And it is the album that I know. I’m not old enough to have watched Bagpuss as a kid, and I’ve since only ever caught glimpses of it on clip shows and the like. I actually rather stumbled upon this album, after hearing a very small snippet of a piece from it on a telly programme by Charlie Brooker and wanting to hear more of it. I wasn’t expecting it to be such a full-on folk fest. This happened during my slow blossoming into a folk music fan (which I’ve discussed a little before) and this album certainly helped me along the way.

The music really does reflect the nature of animator Oliver Postgate’s work: it is utterly charming and delightfully whimsical. There are silly little songs like the ‘mouse rounds’ (rounds, sung by mice, of course), to songs that would sound traditional if their subject matter was ever-so-slightly less surreal, such as ‘Uncle Feedle’ and ‘The Bony King of Nowhere’. There’s also occasional little spoken word bits and pieces from the wonderfully rounded voice of Postgate himself. It’s all so comforting and relaxing, and although the music’s themes are obviously child-friendly, the music itself is not dumbed down for the younger audience at all. This respect for its audience also means that Bagpuss: The Songs and Music is a fulfilling listen for music fans of any age.

Wednesday, 24 April 2019

114: People, Hell and Angels, by Jimi Hendrix

Jimi Hendrix (USA)

People, Hell and Angels (2013)

12 tracks, 53 minutes

Spotify • iTunes

There must surely be hundreds of Jimi Hendrix compilations out there, and a good handful of those are made up of never-before-heard studio bits and bobs, and People, Hell and Angels is one of those. It’s much better than some though. The songs presented here are work-in-progress versions of pieces that were intended to go on his fourth studio album, the production of which was cancelled abruptly for unavoidable, mortality-related reasons. With Jimi’s famed perfection, though, you’d barely guess that these were unfinished.

Come on. You know that the stuff on here is going to be top notch – he was the greatest guitarist of all-time, and even his unstructured jams reach heights most players can never hope to achieve, so when it was with an album in mind, it had to be the next level, and that’s what you get here.

Although Jimi was always a blues guitarist at heart, that’s a more obvious focus here than on his other releases, and a good deal of the tracks here are straight-up blues. There’s a lovely version of ‘Hear My Train A Comin’’ (although it’s never going to be able to live up to the impromptu acoustic 12-string version he did – for my money, one of the greatest tracks of all time), and a cover of Elmore James’ ‘Bleeding Heart.’ But what I find most interesting about this album are his excursions into full-on R’n’B, where we get to hear Jimi play in a way he hadn’t since his days as a backing band staple.

Two tracks stand out in particular. There is ‘Mojo Man’, with a full horn section, percussion and even piano played by NOLA legend James Booker, that’s got a real funk to it, but the show stopper is ‘Let Me Move You’. It’s seven minutes of no-frills, hard-rocking R’n’B, with screaming vocals and honking sax from Lonnie Youngblood. It’s just a massive amount of fun. We all know Jimi’s immense skills as a lead guitarist and bandleader, but this piece lets us see a different side of him: Hendrix as sideman. He’s effortlessly excellent in that role too, of course. He takes some solos and enjoys some noodling around behind Youngblood’s singing occasionally, but even when he is working rhythm guitar duties, he brings a flair that is nigh-unmatched.

Hearing Jimi playing in this different setting just makes it even more painfully obvious how much we lost upon his death at just 27. He wasn’t just an amazing rock musician; he could slip into any format and excel, and pioneer. What could have been. Luckily, we can still enjoy what was, and really, at quality like this, we’re being spoilt as it is.

People, Hell and Angels (2013)

12 tracks, 53 minutes

Spotify • iTunes

There must surely be hundreds of Jimi Hendrix compilations out there, and a good handful of those are made up of never-before-heard studio bits and bobs, and People, Hell and Angels is one of those. It’s much better than some though. The songs presented here are work-in-progress versions of pieces that were intended to go on his fourth studio album, the production of which was cancelled abruptly for unavoidable, mortality-related reasons. With Jimi’s famed perfection, though, you’d barely guess that these were unfinished.

Come on. You know that the stuff on here is going to be top notch – he was the greatest guitarist of all-time, and even his unstructured jams reach heights most players can never hope to achieve, so when it was with an album in mind, it had to be the next level, and that’s what you get here.

Although Jimi was always a blues guitarist at heart, that’s a more obvious focus here than on his other releases, and a good deal of the tracks here are straight-up blues. There’s a lovely version of ‘Hear My Train A Comin’’ (although it’s never going to be able to live up to the impromptu acoustic 12-string version he did – for my money, one of the greatest tracks of all time), and a cover of Elmore James’ ‘Bleeding Heart.’ But what I find most interesting about this album are his excursions into full-on R’n’B, where we get to hear Jimi play in a way he hadn’t since his days as a backing band staple.

Two tracks stand out in particular. There is ‘Mojo Man’, with a full horn section, percussion and even piano played by NOLA legend James Booker, that’s got a real funk to it, but the show stopper is ‘Let Me Move You’. It’s seven minutes of no-frills, hard-rocking R’n’B, with screaming vocals and honking sax from Lonnie Youngblood. It’s just a massive amount of fun. We all know Jimi’s immense skills as a lead guitarist and bandleader, but this piece lets us see a different side of him: Hendrix as sideman. He’s effortlessly excellent in that role too, of course. He takes some solos and enjoys some noodling around behind Youngblood’s singing occasionally, but even when he is working rhythm guitar duties, he brings a flair that is nigh-unmatched.

Hearing Jimi playing in this different setting just makes it even more painfully obvious how much we lost upon his death at just 27. He wasn’t just an amazing rock musician; he could slip into any format and excel, and pioneer. What could have been. Luckily, we can still enjoy what was, and really, at quality like this, we’re being spoilt as it is.

Tuesday, 23 April 2019

113: Éthiopiques, Vol. 4: Ethio Jazz & Musique Instrumentale, 1969-1974, by Mulatu Astatke

Mulatu Astatke (Ethiopia)

Éthiopiques, Vol. 4: Ethio Jazz & Musique Instrumentale, 1969-1974 (1998)

14 tracks, 66 minutes

Spotify • iTunes

Ethiopian music from the 60s and 70s has perhaps been one of the most unexpected success stories in 21st century music. Prior to the turn of the century, the music from what is now known as ‘Swinging Addis,’ the golden age of Ethiopian music, was only really known to Ethiopians and a handful of international enthusiasts. Then the Éthiopiques album series began picking up steam; music from the series was used in films and as samples in hip-hop music, and then in 2007 there was the compilation The Very Best of Éthiopiques and suddenly it was everywhere. Every half-way hip city had its own handful of bands playing covers of Ethiopian golden age hits and composing in their own style, and all the old masters of that time were touring far and wide and collaborating with all sorts of different musicians.

The sound that encapsulated the boom was Ethiojazz. It became a buzzword that was used to refer to all of the myriad styles at play during the Swinging Addis period, but Ethiojazz only ever really referred to the music of one man, Mulatu Astatke. Until recently, Ethiojazz was a style all his own, his unique brand of jazz that took the grooves and instrumentation of post-bop and added the rhythms and percussion of the Latin Caribbean and turned it all to sheer magic by basing all the melodies and chords on the traditional five-note qeñet that makes Ethiopian music sound like nothing else.

This fourth volume of the Éthiopiques series reintroduced Mulatu’s Ethiojazz to the world, and it sent that world crazy. There are many different ensembles on this disc, and the tracks were recorded over many different sessions, in both Ethiopia and the US, but they’re all connected by Mulatu’s presence – by his vision, his compositions, his skills as an arranger and bandleader and his contributions on vibraphone, electric piano and percussion.

After this album came out, Mulatu had a proper resurgence that continues to this day. He’s worked with artists from all over the world and recorded several new albums, but as a compilation of his most fruitful period, Éthiopiques, Vol. 4 is basically perfect, and every track that it includes is infectious in its own way; it even created hits of several pieces including ‘Yègellé Tezeta’, ‘Yèkèrmo Sèw’ and ‘Yèkatit.’ Ethiojazz isn’t just for Ethiopians anymore, and that global appeal wouldn’t have been possible without the music of Mulatu Astatke.

Éthiopiques, Vol. 4: Ethio Jazz & Musique Instrumentale, 1969-1974 (1998)

14 tracks, 66 minutes

Spotify • iTunes

Ethiopian music from the 60s and 70s has perhaps been one of the most unexpected success stories in 21st century music. Prior to the turn of the century, the music from what is now known as ‘Swinging Addis,’ the golden age of Ethiopian music, was only really known to Ethiopians and a handful of international enthusiasts. Then the Éthiopiques album series began picking up steam; music from the series was used in films and as samples in hip-hop music, and then in 2007 there was the compilation The Very Best of Éthiopiques and suddenly it was everywhere. Every half-way hip city had its own handful of bands playing covers of Ethiopian golden age hits and composing in their own style, and all the old masters of that time were touring far and wide and collaborating with all sorts of different musicians.

The sound that encapsulated the boom was Ethiojazz. It became a buzzword that was used to refer to all of the myriad styles at play during the Swinging Addis period, but Ethiojazz only ever really referred to the music of one man, Mulatu Astatke. Until recently, Ethiojazz was a style all his own, his unique brand of jazz that took the grooves and instrumentation of post-bop and added the rhythms and percussion of the Latin Caribbean and turned it all to sheer magic by basing all the melodies and chords on the traditional five-note qeñet that makes Ethiopian music sound like nothing else.

This fourth volume of the Éthiopiques series reintroduced Mulatu’s Ethiojazz to the world, and it sent that world crazy. There are many different ensembles on this disc, and the tracks were recorded over many different sessions, in both Ethiopia and the US, but they’re all connected by Mulatu’s presence – by his vision, his compositions, his skills as an arranger and bandleader and his contributions on vibraphone, electric piano and percussion.

After this album came out, Mulatu had a proper resurgence that continues to this day. He’s worked with artists from all over the world and recorded several new albums, but as a compilation of his most fruitful period, Éthiopiques, Vol. 4 is basically perfect, and every track that it includes is infectious in its own way; it even created hits of several pieces including ‘Yègellé Tezeta’, ‘Yèkèrmo Sèw’ and ‘Yèkatit.’ Ethiojazz isn’t just for Ethiopians anymore, and that global appeal wouldn’t have been possible without the music of Mulatu Astatke.

Monday, 22 April 2019

112: Violins from the Andes, by Familia Pillco

Familia Pillco (Peru)

Violins from the Andes (2001)

15 tracks, 74 minutes

Spotify

I’ve been really excited for this album to come up, and to tell you all about it. It’s a truly wonderful album that is nowhere near as well-known as it should be. In fact, it’s basically fallen into obscurity.

I came across this album in the basement of a previous workplace, literally covered in dust, among hundreds of similarly forgotten discs received in years past. I obviously couldn’t take all of them, so I just grabbed some that I thought looked interesting. I don’t really know why I picked up Violins from the Andes, and I definitely didn’t expect it to sound like this. Right from the first track, I was hooked.

That opening piece, ‘Pasacalle’, is so gorgeous. It’s straight in with two violins playing such fragile harmonies and they are absolutely gut-wrenching. They play in unison sometimes, break apart and come back together, or maybe they are playing similar melodies in different registers, but each dancing and twirling around the tune in their own way. The constant switching from major to minor keys gives it all a real melancholy feel. When I listen to this track, it makes me feel so sad, and I love that instrumental music can play with my emotions that way. The rest of the album carries on in the same vein.

But what is it? I don’t really know that much about it, and because this album is quite obscure now, it’s hard to come across any solid info on the internet either. But I’ll give it a shot…

Familia Pillco, on this album at least, are Reynaldo and Enrique Pillco, a father and son from Cusco, Peru. Both violinists, their music is a fascinating combination of the traditional music of the Incas and other native Andean cultures (think quena flutes and panpipes) adapted to fit within the classical dance styles brought to the region by European colonisers. The rhythms and the forms are those of waltzes, pasacalles and the like, and the tunes are yaravis and huaynos. Even though these are dances, the pieces range from slow to moderate; there’s nothing super-fast on the album, and everything feels very controlled and stately.

As well as the two violins, there’s also usually a guitar or harp solidifying the rhythms and chords in the background, and they also get their moments to shine, which is pleasant. There are times when the violins play on their own, though, such as the piece ‘Uskapauqar’, which take the emotional intensity to the next level. Listen to that track in the right frame of mind and you’ll be in absolute floods.

I really, really wish this music was better known. It is outstanding and touches me right to the heart; surely it must touch others in the same way? Please let me know I’m not alone! Regardless, it seems like such a shame that these musicians and their unique style should not gain wider recognition. I can’t find any other recordings of Familia Pillco or any other musicians that even approach them in terms of style or accomplishment. If you can help, please do get in touch.

Violins from the Andes (2001)

15 tracks, 74 minutes

Spotify

I’ve been really excited for this album to come up, and to tell you all about it. It’s a truly wonderful album that is nowhere near as well-known as it should be. In fact, it’s basically fallen into obscurity.

I came across this album in the basement of a previous workplace, literally covered in dust, among hundreds of similarly forgotten discs received in years past. I obviously couldn’t take all of them, so I just grabbed some that I thought looked interesting. I don’t really know why I picked up Violins from the Andes, and I definitely didn’t expect it to sound like this. Right from the first track, I was hooked.

That opening piece, ‘Pasacalle’, is so gorgeous. It’s straight in with two violins playing such fragile harmonies and they are absolutely gut-wrenching. They play in unison sometimes, break apart and come back together, or maybe they are playing similar melodies in different registers, but each dancing and twirling around the tune in their own way. The constant switching from major to minor keys gives it all a real melancholy feel. When I listen to this track, it makes me feel so sad, and I love that instrumental music can play with my emotions that way. The rest of the album carries on in the same vein.

But what is it? I don’t really know that much about it, and because this album is quite obscure now, it’s hard to come across any solid info on the internet either. But I’ll give it a shot…

Familia Pillco, on this album at least, are Reynaldo and Enrique Pillco, a father and son from Cusco, Peru. Both violinists, their music is a fascinating combination of the traditional music of the Incas and other native Andean cultures (think quena flutes and panpipes) adapted to fit within the classical dance styles brought to the region by European colonisers. The rhythms and the forms are those of waltzes, pasacalles and the like, and the tunes are yaravis and huaynos. Even though these are dances, the pieces range from slow to moderate; there’s nothing super-fast on the album, and everything feels very controlled and stately.

As well as the two violins, there’s also usually a guitar or harp solidifying the rhythms and chords in the background, and they also get their moments to shine, which is pleasant. There are times when the violins play on their own, though, such as the piece ‘Uskapauqar’, which take the emotional intensity to the next level. Listen to that track in the right frame of mind and you’ll be in absolute floods.

I really, really wish this music was better known. It is outstanding and touches me right to the heart; surely it must touch others in the same way? Please let me know I’m not alone! Regardless, it seems like such a shame that these musicians and their unique style should not gain wider recognition. I can’t find any other recordings of Familia Pillco or any other musicians that even approach them in terms of style or accomplishment. If you can help, please do get in touch.

Sunday, 21 April 2019

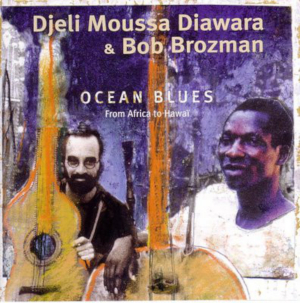

111: Ocean Blues, by Djeli Moussa Diawara & Bob Brozman

Djeli Moussa Diawara & Bob Brozman (Guinea/USA)

Ocean Blues (2000)

11 tracks, 56 minutes

YouTube playlist

As well as being one of the most accomplished slide guitarists in the blues and Hawaiian idioms, Bob Brozman was also a master collaborator. In his career, he released successful albums with musicians from around the world, such as the Tau Moe family (Samoa/Hawaii), Takashi Hirayasu (Okinawa), René Lecaille (La Réunion) and Debashish Bhattacharya (India), always bringing his command of the slide into respectful and equal meetings with his co-performers. Ocean Blues marked the first time he had recorded a collaboration outside of the blues and Hawaiian music spheres, with the famed Guinean kora player Djeli Moussa Diawara.

Considering the sheer number of collaborations between blues musicians and West African musicians that are available these days, it is impressive that Ocean Blues still holds up as one of the best. I think it’s because it isn’t trying to force something that doesn’t have to be there; Diawara and Brozman are not looking to find a perfect mid-point between their respective styles that harks back to a time when the blues was an African music. Instead, they know what they’re good at and that’s what they play: some are traditional Mandé kora pieces, some are blueses and some are from different traditions altogether, bringing in Spanish, Arabic, Mexican or Hawaiian influences; there’s even a beautiful version of the Swahili song ‘Malaika’.

That said, my favourite pieces on the album are actually the two that bring the most blues into their sound, ‘Maloyan Devil’ and ‘Uncle Joe’. The former is based on the Skip James classic ‘Devil Got My Woman’ and the latter was made famous by the calypso singer Wilmoth Houdini, who recorded the piece in 1945. Both of these pieces show the best of the instrumental prowesses of Diawara and Brozman, with multiple exciting solos each, the intricate kora runs melding perfectly with silky slides. Come to think of it, both of these songs are mostly based on the minor I-V7-I chord progression. It’s possibly the most basic chord pattern there is, but it’s also the most effective – it is literally just wave after wave of tension and release. No wonder it’s so good for jamming on; I get the feeling that they could have just played these two tracks for hours if the CD was long enough.

Jamming is essentially what it is too. Aside from Brozman’s multitracked beds of ukuleles, mandolins and all manner of guitars (which were all recorded later), the basis of all the tracks on the album comes from as close to an unencumbered collaboration as possible. The pair recorded the tracks as-live, and they made a point of keeping their rehearsals and practice takes to a strict minimum, to ensure the electricity of the performance was kept in the recordings. It worked too, and also aids the equality of the collaboration in some way; with neither musician entirely certain what magic the other will come out with next, everything is approached on an equal footing. So many West African blues experiments fall flat through over-mediation, with everyone involved trying to second-guess what their music should sound like. On Ocean Blues, Djeli Moussa Diawara and Bob Brozman show them how it’s done with the utmost of class.

Ocean Blues (2000)

11 tracks, 56 minutes

YouTube playlist

As well as being one of the most accomplished slide guitarists in the blues and Hawaiian idioms, Bob Brozman was also a master collaborator. In his career, he released successful albums with musicians from around the world, such as the Tau Moe family (Samoa/Hawaii), Takashi Hirayasu (Okinawa), René Lecaille (La Réunion) and Debashish Bhattacharya (India), always bringing his command of the slide into respectful and equal meetings with his co-performers. Ocean Blues marked the first time he had recorded a collaboration outside of the blues and Hawaiian music spheres, with the famed Guinean kora player Djeli Moussa Diawara.

Considering the sheer number of collaborations between blues musicians and West African musicians that are available these days, it is impressive that Ocean Blues still holds up as one of the best. I think it’s because it isn’t trying to force something that doesn’t have to be there; Diawara and Brozman are not looking to find a perfect mid-point between their respective styles that harks back to a time when the blues was an African music. Instead, they know what they’re good at and that’s what they play: some are traditional Mandé kora pieces, some are blueses and some are from different traditions altogether, bringing in Spanish, Arabic, Mexican or Hawaiian influences; there’s even a beautiful version of the Swahili song ‘Malaika’.

That said, my favourite pieces on the album are actually the two that bring the most blues into their sound, ‘Maloyan Devil’ and ‘Uncle Joe’. The former is based on the Skip James classic ‘Devil Got My Woman’ and the latter was made famous by the calypso singer Wilmoth Houdini, who recorded the piece in 1945. Both of these pieces show the best of the instrumental prowesses of Diawara and Brozman, with multiple exciting solos each, the intricate kora runs melding perfectly with silky slides. Come to think of it, both of these songs are mostly based on the minor I-V7-I chord progression. It’s possibly the most basic chord pattern there is, but it’s also the most effective – it is literally just wave after wave of tension and release. No wonder it’s so good for jamming on; I get the feeling that they could have just played these two tracks for hours if the CD was long enough.

Jamming is essentially what it is too. Aside from Brozman’s multitracked beds of ukuleles, mandolins and all manner of guitars (which were all recorded later), the basis of all the tracks on the album comes from as close to an unencumbered collaboration as possible. The pair recorded the tracks as-live, and they made a point of keeping their rehearsals and practice takes to a strict minimum, to ensure the electricity of the performance was kept in the recordings. It worked too, and also aids the equality of the collaboration in some way; with neither musician entirely certain what magic the other will come out with next, everything is approached on an equal footing. So many West African blues experiments fall flat through over-mediation, with everyone involved trying to second-guess what their music should sound like. On Ocean Blues, Djeli Moussa Diawara and Bob Brozman show them how it’s done with the utmost of class.

Saturday, 20 April 2019

110: Método Cardiofónico, by Germán Díaz

Germán Díaz (Spain)

Método Cardiofónico (2014)

12 tracks, 46 minutes

Spotify • iTunes

There are many theories that relate human beings’ love for music to its resemblance to their own cardiorhythms. Galician musician Germán Díaz took this idea and ran with it. Díaz’ Método Cardiofónico is certainly high-concept, and it’s not the first of its name. In 1933, Dr Miguel Iriarte recorded many examples of both healthy and afflicted heartbeats onto slate discs. The recordings were then translated onto shellac and published as Método Cardifónico, for the use and training of medical students. Díaz the elder was a doctor, and passed a copy of these shellac discs onto his son; as a master of the zanfona (Galician hurdy-gurdy), Díaz the younger knew he had to find a musical use for the recordings.

Each piece on the resulting album is based around a different rhythm from Dr Iriarte’s collection. From those most organic of musical bases, Díaz looked in the opposite direction, bringing in mechanical music in a big way. Across this album are probably many kilometres of hand-punched card, on which Díaz intricately programmed the parts for the mechanical instruments: there’s a music box, a barrel organ and a ‘chromatic rollmonica,’ an interesting little device that is a little like a harmonica version of a player piano. Here’s a great little film on YouTube explaining all the various processes that went into the making of the album:

Over and above this antique musical cyborg, Díaz and his friends create wonderfully sophisticated yet cheerful chamber jazz. Between them, they add the live sounds of zanfona, trumpet, tuba, clarinets standard and bass, oboe and cor anglais – the latter two of which I usually have a healthy hatred of, but here they sound absolutely lovely. The unusual timbres at play give the music a slightly wonky feel (helped by the occasionally limping heartbeats), and the typewriteresque click-clackery of the zanfona and mechanical gadgets make it feel like it was recorded in the workshop of some hair-brained engineer. Some tracks, such as ‘Cirro’ and ‘Lettre Pour Béatrice’, sound so whimsical they could have come straight out of a Studio Ghibli film soundtrack.

A lot of effort went into this album, from composing and arranging the pieces around the cardiophonics, to the painstaking programming of the mechanical instruments’ parts and even their fine-tuning to work with an ensemble, to the perfect balancing of the instruments and the techniques to incorporate in to solos to create and curate a very unique atmosphere. I’m not sure I can name another album that even tries to approach what this one achieves. Well done Germán Díaz. I ❤️ Método Cardiofónico.

Método Cardiofónico (2014)

12 tracks, 46 minutes

Spotify • iTunes

There are many theories that relate human beings’ love for music to its resemblance to their own cardiorhythms. Galician musician Germán Díaz took this idea and ran with it. Díaz’ Método Cardiofónico is certainly high-concept, and it’s not the first of its name. In 1933, Dr Miguel Iriarte recorded many examples of both healthy and afflicted heartbeats onto slate discs. The recordings were then translated onto shellac and published as Método Cardifónico, for the use and training of medical students. Díaz the elder was a doctor, and passed a copy of these shellac discs onto his son; as a master of the zanfona (Galician hurdy-gurdy), Díaz the younger knew he had to find a musical use for the recordings.

Each piece on the resulting album is based around a different rhythm from Dr Iriarte’s collection. From those most organic of musical bases, Díaz looked in the opposite direction, bringing in mechanical music in a big way. Across this album are probably many kilometres of hand-punched card, on which Díaz intricately programmed the parts for the mechanical instruments: there’s a music box, a barrel organ and a ‘chromatic rollmonica,’ an interesting little device that is a little like a harmonica version of a player piano. Here’s a great little film on YouTube explaining all the various processes that went into the making of the album:

Over and above this antique musical cyborg, Díaz and his friends create wonderfully sophisticated yet cheerful chamber jazz. Between them, they add the live sounds of zanfona, trumpet, tuba, clarinets standard and bass, oboe and cor anglais – the latter two of which I usually have a healthy hatred of, but here they sound absolutely lovely. The unusual timbres at play give the music a slightly wonky feel (helped by the occasionally limping heartbeats), and the typewriteresque click-clackery of the zanfona and mechanical gadgets make it feel like it was recorded in the workshop of some hair-brained engineer. Some tracks, such as ‘Cirro’ and ‘Lettre Pour Béatrice’, sound so whimsical they could have come straight out of a Studio Ghibli film soundtrack.

A lot of effort went into this album, from composing and arranging the pieces around the cardiophonics, to the painstaking programming of the mechanical instruments’ parts and even their fine-tuning to work with an ensemble, to the perfect balancing of the instruments and the techniques to incorporate in to solos to create and curate a very unique atmosphere. I’m not sure I can name another album that even tries to approach what this one achieves. Well done Germán Díaz. I ❤️ Método Cardiofónico.

Friday, 19 April 2019

109: Les Tambourinaires du Burundi, by the Drummers of Burundi

The Drummers of Burundi (Burundi)

Les Tambourinaires du Burundi (1992)

1 track, 31 minutes

Bandcamp • Spotify • iTunes

Watching the Drummers of Burundi is a spectacle that is hard to forget. You hear them before you see them – a distant booming coming closer and closer, joined by the high-pitched clacking of wood-on-wood as it gets nearer. Then you see them and it’s even more striking than that powerful sound had you expecting. A big bunch of willowy, muscular men in beautiful robes of white, red and green to match the Burundian flag, each with a gigantic wooden drum on their head, playing their infectious beat with all their might. Now there’s an indelible image.

They set their karyenda drums in a semi-circle with one (painted with the flag) in the middle for soloists, and the energy levels never let up. They keep their beat going as long as you’d like, the drummers taking turns to play different aspects of the rhythms, to solo on the main drum and to impress with acrobatic flips, jumping splits and dancing with spears and shields. At the end, they load the drums back on to their heads and troop away, never letting that beat waver. There are few musical experiences that can match watching – and feeling – the Drummers of Burundi.

And so we come to this album. It was recorded in Real World Studios in 1987, completely live – to be honest, there isn’t really any other way to record 20 drummers of this particular might. As such, you don’t hear anything that wouldn’t be there in a live performance, although there isn’t the wonderful incoming and outgoing head-bound drumming; I guess it wouldn’t have the same effect on record. There is a short call-and-response to start, the leader asking the others if they are ready and worthy to play these royal and sacred drums. Everyone decides that, yes, they’re pretty sure they are and they get to it. It is a beat that will get all the way through your body (if you play it loud enough) and the ever-evolving rhythmic patterns will do something pleasant to your brain, too. As it’s a live performance, it’s presented as one long, unbroken track – what is a little strange that it is only 30 minutes, considering that they can go for much, much longer.

If you’ve never heard the Drummers of Burundi before but the music on this album sounds familiar to you, you might be right. This album was not the first time the music of the karyenda drummers was heard in Europe, and it was most famously included in the Ocora album Musiques du Burundi in 1968. That recording became a sort of cult hit in certain circles and ended up being one of the most unlikely sources of inspiration among new wave and post-punk musicians. The rhythms of what was called ‘the Burundi Beat’ became infused into the work of bands such as Bow Wow Wow and Adam and the Ants.

Those groups had their own thing going on, but their rhythms just don’t match the Drummers for the sheer intensity and awesomeness. Of course this album is never going to fully capture what these musicians do live – the power of their beats and the chest-rattling reverberations can only ever be experienced within earshot of the actual drum – but it certainly captures a little bit of what they’re about and the mesmerising qualities of their sound.

Les Tambourinaires du Burundi (1992)

1 track, 31 minutes

Bandcamp • Spotify • iTunes

Watching the Drummers of Burundi is a spectacle that is hard to forget. You hear them before you see them – a distant booming coming closer and closer, joined by the high-pitched clacking of wood-on-wood as it gets nearer. Then you see them and it’s even more striking than that powerful sound had you expecting. A big bunch of willowy, muscular men in beautiful robes of white, red and green to match the Burundian flag, each with a gigantic wooden drum on their head, playing their infectious beat with all their might. Now there’s an indelible image.

They set their karyenda drums in a semi-circle with one (painted with the flag) in the middle for soloists, and the energy levels never let up. They keep their beat going as long as you’d like, the drummers taking turns to play different aspects of the rhythms, to solo on the main drum and to impress with acrobatic flips, jumping splits and dancing with spears and shields. At the end, they load the drums back on to their heads and troop away, never letting that beat waver. There are few musical experiences that can match watching – and feeling – the Drummers of Burundi.

And so we come to this album. It was recorded in Real World Studios in 1987, completely live – to be honest, there isn’t really any other way to record 20 drummers of this particular might. As such, you don’t hear anything that wouldn’t be there in a live performance, although there isn’t the wonderful incoming and outgoing head-bound drumming; I guess it wouldn’t have the same effect on record. There is a short call-and-response to start, the leader asking the others if they are ready and worthy to play these royal and sacred drums. Everyone decides that, yes, they’re pretty sure they are and they get to it. It is a beat that will get all the way through your body (if you play it loud enough) and the ever-evolving rhythmic patterns will do something pleasant to your brain, too. As it’s a live performance, it’s presented as one long, unbroken track – what is a little strange that it is only 30 minutes, considering that they can go for much, much longer.

If you’ve never heard the Drummers of Burundi before but the music on this album sounds familiar to you, you might be right. This album was not the first time the music of the karyenda drummers was heard in Europe, and it was most famously included in the Ocora album Musiques du Burundi in 1968. That recording became a sort of cult hit in certain circles and ended up being one of the most unlikely sources of inspiration among new wave and post-punk musicians. The rhythms of what was called ‘the Burundi Beat’ became infused into the work of bands such as Bow Wow Wow and Adam and the Ants.

Those groups had their own thing going on, but their rhythms just don’t match the Drummers for the sheer intensity and awesomeness. Of course this album is never going to fully capture what these musicians do live – the power of their beats and the chest-rattling reverberations can only ever be experienced within earshot of the actual drum – but it certainly captures a little bit of what they’re about and the mesmerising qualities of their sound.

Thursday, 18 April 2019

108: Together Again: Legends of Bulgarian Wedding Music, by Ivo Papasov & Yuri Yunakov

Ivo Papasov & Yuri Yunakov (Bulgaria)

Together Again: Legends of Bulgarian Wedding Music (2005)

8 tracks, 53 minutes

Spotify • iTunes

There’s been a few examples of wedding music on this blog so far, and they all make for a much better party than Wagner on the organ and Abba in the disco. Although Together Again credits Ivo Papasov and Yuri Yunakov as the main artists, the core group at play is actually a quartet: Papasov on clarinet, Yunakov on alto sax, Salif Ali on drums and Neshko Neshev on accordion. They are all members of the Turkish Romani population in Bulgaria, and masters of the wedding music and dance styles of ruchenica, horo and stambolovo. As befitting their heritage, their music has all manner of Balkan, Middle Eastern and Romani influences, as well as taking cues from jazz, rock and funk in little pieces here and there.

The album gets off to an incredible start with the piece ‘Oriental’. It begins with a fill between the darbuka and drum kit, and then it’s off at a million miles an hour – I calculate it at about 332 beats per minute. Papasov, Yunakov and Neshev play the main melody in heterophony; that is, they are all playing the same tune, but all improvising minute ornaments and embellishments along the way. Given that the melody is already quite intricate and then factoring in the pace of the whole thing, the effect is astounding. It slows down a little bit for the beginning of the sax solo, but it’s back up to speed before long, and the way that the guitar (from Kalin Kirilov) and drums work together towards the end even resembles some sort of speed-funk.

What is striking all the way through is the simply stunning virtuosity. It doesn’t matter who is soloing, the level is the same: the notes flow thick and fast and chords and scales change so rapidly, but it’s never devoid of emotion, even if that emotion is usually to do with partying. Despite me saying that I don’t know much about the region’s music, I do seem to have featured quite a bit of Eastern European music on here, and I think this is one of the reasons why. To even be able to perform the styles on display on this album even competently, you already need to be a top-class musician. To be able to imbue each lightning-fast note with feeling, then, and to create exciting, dynamic and inventive solos on top of it all shows some serious genius at work.

Together Again: Legends of Bulgarian Wedding Music (2005)

8 tracks, 53 minutes

Spotify • iTunes

There’s been a few examples of wedding music on this blog so far, and they all make for a much better party than Wagner on the organ and Abba in the disco. Although Together Again credits Ivo Papasov and Yuri Yunakov as the main artists, the core group at play is actually a quartet: Papasov on clarinet, Yunakov on alto sax, Salif Ali on drums and Neshko Neshev on accordion. They are all members of the Turkish Romani population in Bulgaria, and masters of the wedding music and dance styles of ruchenica, horo and stambolovo. As befitting their heritage, their music has all manner of Balkan, Middle Eastern and Romani influences, as well as taking cues from jazz, rock and funk in little pieces here and there.

The album gets off to an incredible start with the piece ‘Oriental’. It begins with a fill between the darbuka and drum kit, and then it’s off at a million miles an hour – I calculate it at about 332 beats per minute. Papasov, Yunakov and Neshev play the main melody in heterophony; that is, they are all playing the same tune, but all improvising minute ornaments and embellishments along the way. Given that the melody is already quite intricate and then factoring in the pace of the whole thing, the effect is astounding. It slows down a little bit for the beginning of the sax solo, but it’s back up to speed before long, and the way that the guitar (from Kalin Kirilov) and drums work together towards the end even resembles some sort of speed-funk.

What is striking all the way through is the simply stunning virtuosity. It doesn’t matter who is soloing, the level is the same: the notes flow thick and fast and chords and scales change so rapidly, but it’s never devoid of emotion, even if that emotion is usually to do with partying. Despite me saying that I don’t know much about the region’s music, I do seem to have featured quite a bit of Eastern European music on here, and I think this is one of the reasons why. To even be able to perform the styles on display on this album even competently, you already need to be a top-class musician. To be able to imbue each lightning-fast note with feeling, then, and to create exciting, dynamic and inventive solos on top of it all shows some serious genius at work.

Wednesday, 17 April 2019

107: Churchical Chants of the Nyabingi, by the Church Triumphant of Jah Rastafari

Church Triumphant of Jah Rastafari (Jamaica)

Churchical Chants of the Nyabingi (1983)

10 tracks, 42 minutes

YouTube playlist

We know a lot of Rastafari religious music in the form of roots reggae, but it’s not that often that we hear much of the ritual music of the Rasta church, the nyabinghi. This album is a great place to start. It’s a recording of an actual ritual – one of the biggest ever nyabinghi gatherings, as it happens – and so it captures the true musical form of the worship. A particularly interesting element of this recording is its context: the reason it was such a big gathering was in response to a visit to Jamaica by Ronald Reagan in 1982, during his presidency. The event was a reaction against the honour with which the Jamaican government was receiving its guest. As such, the songs that are on this record are not only chants to Jah and to Ras Tafari, Haile Selassie I, but they’re also filled with righteous anger directed at Reagan, the Pope and religious and white supremacist imperialism in general. The whole gathering lasted for seven days. Heavy stuff.

The music itself is all percussion and voice. The percussion is made up of three types of drums and various rattles and shakers that bring strongly to mind West African drum ensembles. The voice, however, is really a mix of things: there is lots of overlapping call-and-response between the leader and the congregation, but the harmonies and melodies obviously owe lots to the Christian tradition of hymns. The whole effect make the nyabinghi bear a lot of musical resemblance to the spiritual music of other Afrodiasporic religions in the Americas, especially Vodou in Haiti but also to some degree Santería in Cuba and Candomblé in Brazil. Rastafari is a bit different from those religions though; whereas the others developed organically from West African religions (most notably of the Ewe, Yoruba and Fon) incorporating elements of Christian practice and imagery to ‘hide in plain sight’ when the Africans’ religious practices were banned, Rastafari was somewhat more explicit in its construction, with its religious practices and rituals built from pre-existing cultural elements of Christian, Ethiopian, West African and Afrodiasporic religions as well as secular political beliefs. It’s not impossible that nyabinghi was directly influenced by the music of Vodou and similar traditions.

Listening to nyabinghi also allows for a bit of a glimpse into the creation of reggae: you can hear how, with the addition of influences from soul, gospel and rock music, this style could move towards the direction of roots reggae. But then again, this recording was made in the 1980s, when reggae was already a huge phenomenon. However it came about, and whichever cultural factors were at play Churchical Chants of the Nyabingi is a great document of a particular and epic event, and also a great document of a deep religious practice that is widely known of, but not often known about, at least in any detail.

Churchical Chants of the Nyabingi (1983)

10 tracks, 42 minutes

YouTube playlist

We know a lot of Rastafari religious music in the form of roots reggae, but it’s not that often that we hear much of the ritual music of the Rasta church, the nyabinghi. This album is a great place to start. It’s a recording of an actual ritual – one of the biggest ever nyabinghi gatherings, as it happens – and so it captures the true musical form of the worship. A particularly interesting element of this recording is its context: the reason it was such a big gathering was in response to a visit to Jamaica by Ronald Reagan in 1982, during his presidency. The event was a reaction against the honour with which the Jamaican government was receiving its guest. As such, the songs that are on this record are not only chants to Jah and to Ras Tafari, Haile Selassie I, but they’re also filled with righteous anger directed at Reagan, the Pope and religious and white supremacist imperialism in general. The whole gathering lasted for seven days. Heavy stuff.

The music itself is all percussion and voice. The percussion is made up of three types of drums and various rattles and shakers that bring strongly to mind West African drum ensembles. The voice, however, is really a mix of things: there is lots of overlapping call-and-response between the leader and the congregation, but the harmonies and melodies obviously owe lots to the Christian tradition of hymns. The whole effect make the nyabinghi bear a lot of musical resemblance to the spiritual music of other Afrodiasporic religions in the Americas, especially Vodou in Haiti but also to some degree Santería in Cuba and Candomblé in Brazil. Rastafari is a bit different from those religions though; whereas the others developed organically from West African religions (most notably of the Ewe, Yoruba and Fon) incorporating elements of Christian practice and imagery to ‘hide in plain sight’ when the Africans’ religious practices were banned, Rastafari was somewhat more explicit in its construction, with its religious practices and rituals built from pre-existing cultural elements of Christian, Ethiopian, West African and Afrodiasporic religions as well as secular political beliefs. It’s not impossible that nyabinghi was directly influenced by the music of Vodou and similar traditions.

Listening to nyabinghi also allows for a bit of a glimpse into the creation of reggae: you can hear how, with the addition of influences from soul, gospel and rock music, this style could move towards the direction of roots reggae. But then again, this recording was made in the 1980s, when reggae was already a huge phenomenon. However it came about, and whichever cultural factors were at play Churchical Chants of the Nyabingi is a great document of a particular and epic event, and also a great document of a deep religious practice that is widely known of, but not often known about, at least in any detail.

Tuesday, 16 April 2019

106: The Bressingham Voigt

The Bressingham Voigt (1976)

13 tracks, 53 minutes

Stream or download on Archive.org

I think this is only one of two albums on the list that don’t actually have an ‘artist’ as such: all the music on this one is played by steam. To be more precise, it’s steam as pumped through a Voigt Ruth Model 35a 69-Keyless Band Organ, built in 1930. The organ was built in Germany, lived in Bressingham Gardens and Steam Museum for most of its time (hence the name), and was bought in 2002 by a collector in the Netherlands, where it still performs regularly.

The sound of the thing is really charming. There are loads of organ pipes of different timbres, including flutes, trompettes, oboes and strings, all with different types of tremolo available to them; there’s also a xylophone in there and a snare drum and some cymbals. And all of those are programmed into hole-punched reels – I can only imagine the amount of meticulous effort that goes into programming all that; unfortunately the name of the programmer has been lost to time. They’re not simple pieces either. The repertoire on this album is a mixture of mostly light classical pieces, Viennese waltzes, chamber dance styles and marches, mostly, although there are some outliers, such as a ‘Medley of 1954’ of some pop tunes of the day, including Hank William’s ‘Jambalaya On The Bayou’. It’s all so cheerful!

But let’s be honest, I didn’t stumble across this album out of the blue, or from a pre-existing love of mechanical music as such. No, it’s another video game soundtrack! The game Rollercoaster Tycoon from 1999* is a theme park building and management sim, and it’s one of the most perfect games of all time – it’s perfectly weighted, it’s challenging while still being incredibly relaxing and it has a wonderful aesthetic. It doesn’t have music of a soundtrack though, aside from a theme tune when you boot up the game and ambient noises of the theme park you’ve created. And that’s where this album comes in. The only music featured in the game itself is played whenever you have a merry-go-round going in your park. When it came to choosing what sounds the ride made, developer Chris Sawyer remembered an album in his dad’s record collection that would fit the bill; that was The Bressingham Voigt and so all the music in the game is just taken directly from this album.

Like the humongous dweeb that I am, when I learnt that the music from Rollercoaster Tycoon wasn’t just available as an album, but on an old vinyl from 1976, I had to get my hands on it. And I did! Pleasingly cheap too, from discogs, although now you can download it directly from Archive.org.

People have told me that they think it’s creepy – it reminds them of abandoned fairgrounds and killer clowns, they say – and I understand that a little bit, but for me it’s just too jolly! I guess it helps that it’s connected to hours and hours of Rollercoaster Tycoon in my head, but very little of the music that I listen to is so unabashedly light-hearted, so considering I’ve found some, I want to hold on to that. It’s just steam, a load of pipes and some really wholesome noises coming out of them. And if it doesn’t make you want to ride on a creaking wooden merry-go-round to feel the wind rushing through your Victorian pin-curls with one of those comically-sized lollipops in hand…well, maybe you had a bad experience with a clown when you were little, I dunno.

*It was actually released 20 years ago to the day that I’m writing this – cool!

13 tracks, 53 minutes

Stream or download on Archive.org

I think this is only one of two albums on the list that don’t actually have an ‘artist’ as such: all the music on this one is played by steam. To be more precise, it’s steam as pumped through a Voigt Ruth Model 35a 69-Keyless Band Organ, built in 1930. The organ was built in Germany, lived in Bressingham Gardens and Steam Museum for most of its time (hence the name), and was bought in 2002 by a collector in the Netherlands, where it still performs regularly.

The sound of the thing is really charming. There are loads of organ pipes of different timbres, including flutes, trompettes, oboes and strings, all with different types of tremolo available to them; there’s also a xylophone in there and a snare drum and some cymbals. And all of those are programmed into hole-punched reels – I can only imagine the amount of meticulous effort that goes into programming all that; unfortunately the name of the programmer has been lost to time. They’re not simple pieces either. The repertoire on this album is a mixture of mostly light classical pieces, Viennese waltzes, chamber dance styles and marches, mostly, although there are some outliers, such as a ‘Medley of 1954’ of some pop tunes of the day, including Hank William’s ‘Jambalaya On The Bayou’. It’s all so cheerful!

But let’s be honest, I didn’t stumble across this album out of the blue, or from a pre-existing love of mechanical music as such. No, it’s another video game soundtrack! The game Rollercoaster Tycoon from 1999* is a theme park building and management sim, and it’s one of the most perfect games of all time – it’s perfectly weighted, it’s challenging while still being incredibly relaxing and it has a wonderful aesthetic. It doesn’t have music of a soundtrack though, aside from a theme tune when you boot up the game and ambient noises of the theme park you’ve created. And that’s where this album comes in. The only music featured in the game itself is played whenever you have a merry-go-round going in your park. When it came to choosing what sounds the ride made, developer Chris Sawyer remembered an album in his dad’s record collection that would fit the bill; that was The Bressingham Voigt and so all the music in the game is just taken directly from this album.

Like the humongous dweeb that I am, when I learnt that the music from Rollercoaster Tycoon wasn’t just available as an album, but on an old vinyl from 1976, I had to get my hands on it. And I did! Pleasingly cheap too, from discogs, although now you can download it directly from Archive.org.

People have told me that they think it’s creepy – it reminds them of abandoned fairgrounds and killer clowns, they say – and I understand that a little bit, but for me it’s just too jolly! I guess it helps that it’s connected to hours and hours of Rollercoaster Tycoon in my head, but very little of the music that I listen to is so unabashedly light-hearted, so considering I’ve found some, I want to hold on to that. It’s just steam, a load of pipes and some really wholesome noises coming out of them. And if it doesn’t make you want to ride on a creaking wooden merry-go-round to feel the wind rushing through your Victorian pin-curls with one of those comically-sized lollipops in hand…well, maybe you had a bad experience with a clown when you were little, I dunno.

*It was actually released 20 years ago to the day that I’m writing this – cool!

Monday, 15 April 2019

105: Diaspora, by Natacha Atlas

Natacha Atlas (United Kingdom/Egypt)

Diaspora (1995)

12 tracks, 72 minutes

Spotify • iTunes

By the mid-90s, British-Belgian-Egyptian-Israeli singer Natacha Atlas was already a star within the UK’s world dubtronica scene. She was the lead vocalist with several pioneers of the scene, most notably Transglobal Underground and Jah Wobble’s Invaders of the Heart, and had guested with everyone from Loop Guru, Nitin Sawhney, Not Drowning, Waving and Apache Indian. With Diaspora, she struck out on her own with her first debut album…sort of.